There’s no proof of life on the moon Enceladus, which shoots giant geysers of water vapor into space.

But NASA thinks the icy Saturnian satellite is one of the best places to look.

In new research published in Nature Astronomy, planetary scientists investigated detections from the space agency’s Cassini mission, which flew through Enceladus’ watery, carbon-rich plumes. They concluded that the plume, and therefore the ocean below the ice, also contains the vital molecule hydrogen cyanide — “a molecule that is key to the origin of life,” NASA explained.

“Our work provides further evidence that Enceladus is host to some of the most important molecules for both creating the building blocks of life and for sustaining that life through metabolic reactions,” study author Jonah Peter, a doctoral student at Harvard University who worked on this Enceladus research at NASA, said in a statement.

Life on Earth needs amino acids — organic compounds that exist in genetic material and proteins. And hydrogen cyanide is a crucial ingredient in forming amino acids.

Mashable Light Speed

“The discovery of hydrogen cyanide was particularly exciting, because it’s the starting point for most theories on the origin of life,” Peter said.

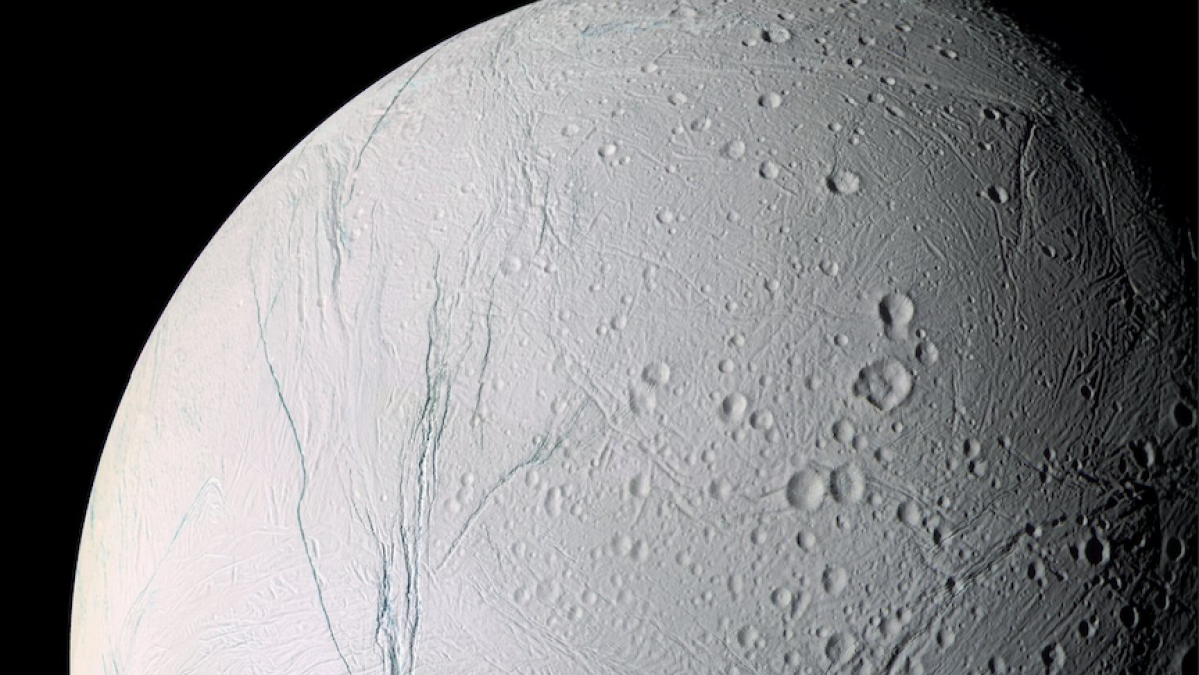

NASA’s Cassini probe captured these jets of water vapor and organic compounds shooting from the moon’s south pole on Nov. 21, 2009.

Credit: NASA / JPL / Space Science Institute

Enceladus, 314 miles (505 km) across, compared to the United Kingdom.

Credit: NASA

Although the Cassini mission ended in 2017, when the spacecraft burned up in Saturn‘s atmosphere, scientists are still dissecting all the data it beamed back to Earth. They already knew the plumes contained lots of water, along with carbon dioxide and methane. But with deeper analysis, they found it contains hydrogen cyanide, too.

But that’s not all.

“Our work provides further evidence that Enceladus is host to some of the most important molecules for both creating the building blocks of life and for sustaining that life through metabolic reactions.”

The researchers also found that the organic compounds (meaning they contain carbon, a common ingredient in life) were altered, specifically “oxidized,” a process that releases energy. In short, this suggests chemical processes in Enceladus’ ocean, which sloshes beneath its ice shell, are “capable of providing a large amount of energy to any life that might be present,” NASA’s Kevin Hand, who coauthored the new research, said in a statement.

Enceladus only grows more intriguing. NASA is now weighing a proposal to send a spacecraft, a project called the Enceladus Orbilander, to this distant moon. The robotic craft would fly around Enceladus, and then land on its mysterious, icy surface.