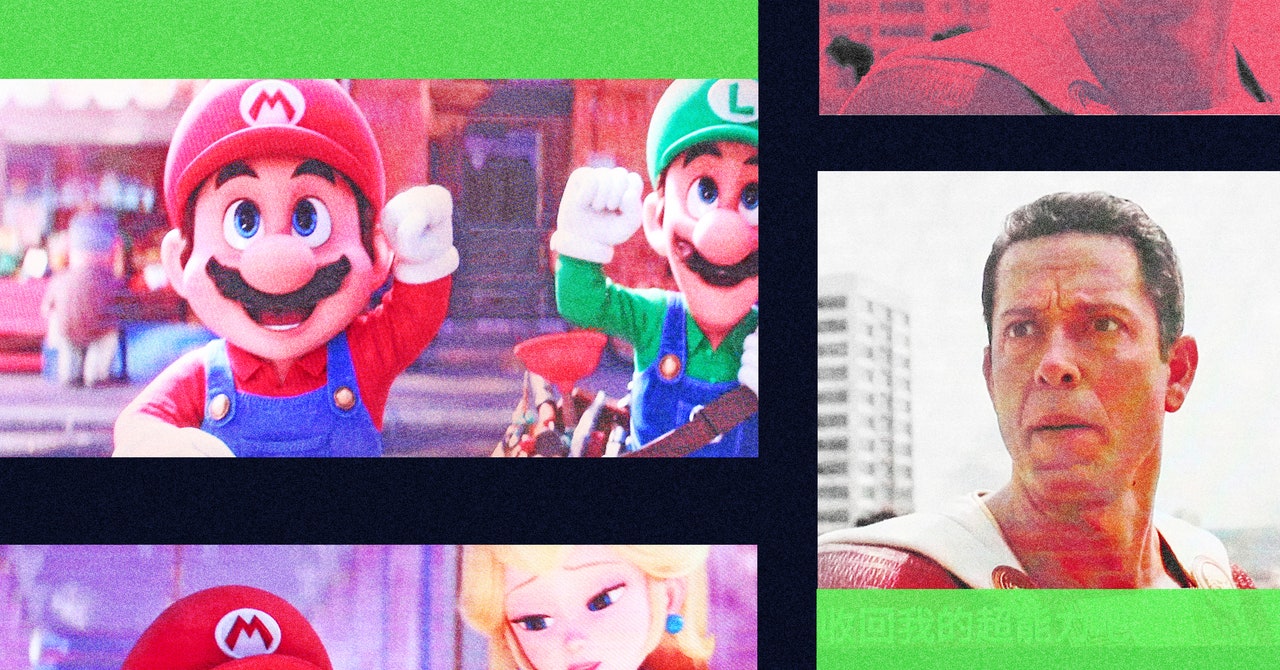

Mario’s success will lead to a “deluge” of video game adaptations, argues Joost van Druenen, a New York University business professor and author of One Up: Creativity, Competition, and the Global Business of Video Games. Van Dreunen reckons that superheroes are “going the way of the cowboy,” referring to the shifts in Hollywood’s dominant genres (think: the rise of zombies a few years back, all the Home Alone-esque family movies in the 1990s). Even a show like The Boys, he argues, with its anti-superheroes, looks like a kind of turning point, akin to the revisionist Westerns, exemplified by Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch, that began to dominate the genre at the end of the ’60s and into the ’70s.

Provided audiences are as tired of superheroes as pundits think, video game protagonists could profitably fill the gap. They come from well-known franchises and have large, engaged fan bases—two things studios appreciate. Cast your eyes down the development list: God of War, Ghost of Tsushima, Assassin’s Creed, continued expansion on The Witcher, among others. Nintendo, which has traditionally resisted film spinoffs, is planning a movie a year; Arcane, widely considered the first title (before The Last of Us) to break the curse of such adaptations, is finally getting a second season. Amazon’s forthcoming Fallout series is being helmed by the same team as Westworld.

“Video game content is now appealing to filmmakers, unlike ever before,” says van Dreunen. “So that’s coming in at the same time the superhero movies are starting to reach their tail end.” Of course, these are not sure things: Gran Turismo’s performance was decidedly average, and it’d be fair to question whether any game character can compete with Mario’s star power. Looking into next year, Fallout will be an early litmus. If it finds a foothold upon release in April, that’ll be the surest sign yet that pop culture is entering its video game adaptation era.

Back to superheroes, artist fatigue is one under-explored factor. Inspiration is lacking. Some are undoubtedly tired of the whole enterprise, but many are just tired of poor films: And clearly, these two factors entwine. “I think it’s the quality of the movie, more so than the superheroes themselves,” says Mark Caplan, who worked in video game licensing for Sony Pictures and Twentieth Century Fox and worked on the three Spider-Man games of the Tobey Maguire era. “Superheroes have always found an audience, whether it’s through paper or through film, television—and it will continue.”

The film critic Richard Brody captured this general listlessness in his lukewarm review of The Marvels. Brody blames copyright restrictions: If artists outside of the multinationals could reimagine superheroes, “fatigue” talk would be moot; that world, unfortunately, is many years away. “What happened to superhero movies?” Brody writes. “How did a genre rooted in astonishment, weirdness, and wonder become a byword for the normative, the familiar, and the mundane?” That’s the astonishment, weirdness, and wonder that game adaptations need to recapture.